My daughter Emily, daughter-in-law Phoebe, and I have taken up the annual April Blogging Challenge, posting Monday through Friday during the month of April. You can catch up with Emily here and Phoebe here.

This is a really long post. I considered posting it in two parts, but it makes more sense in one. Feel free to get a cup of coffee or do a load of laundry partway through.

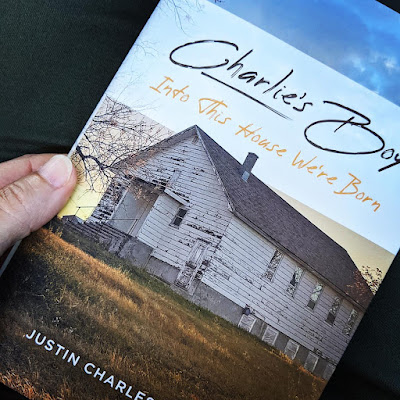

If you only want to read the book review, scroll down to the shot of the book cover.

Diogenes, you might recall, was the guy in Greek legend who walked around with a lamp, looking for an honest man.

Sometimes I think of myself as Dorcogenes, hunting for an honest Mennonite book.

We Anabaptists believe that “faith without works is dead.” Obedience is important, even at great sacrifice, and faith is as important in everyday life as in the specifically holy moments of worship on Sundays.

We also believe in choices leading to consequences, sowing and reaping, and men’s courses foreshadowing certain ends, as Charles Dickens said.

That's what I taught my children: your choices matter.

However, it seems to me we have taken this belief further than God ever intended. We convince ourselves that behaving properly, working hard, and following the rules will always lead to the logical rewards of happy marriages, functional families, good health, prosperity, and respect from others.

This leads, I believe, to a dangerous fallacy: I have the power to make everything turn out ok. And if it doesn’t turn out ok, it’s my fault. It puts us in a God-like position that we were never meant to occupy, and it doesn’t build a foundation of faith for the times when nothing makes sense.

As a culture, we’re not sure what to do with the real-life stories that don’t turn out, the children of good parents who make bad choices, the hard-working carpenters who suffer financial losses, the people who leave our church, or the women in modest cape dresses who were sexually assaulted and/or whose mental health disintegrated.

Do we have a faith that can stay strong even when the sweet married couple struggles with infertility while the alcoholic single mom across the street keeps having babies? What about when we do our best and things still don’t work out? Or when someone else messes up, yet their kids turn out better than mine?

Is there grace for the truth of our lives?

The belief that I can control the outcome by living right manifests itself in Anabaptist literature, from Sunday school flyers with naughty children set back on the straight and narrow to biographies and how-to books.

Here are two examples, and if you want actual titles and such, you can message me. I'm trying to verify my statements without unduly discouraging the authors, which might be impossible. I’m not saying that these books didn’t have good qualities or interesting content, but they both had that disturbing theme.

Paul recently read a book about local family and church history. Full of authentic old letters and other historical documents, the book seemed factual and objective at first glance and was an interesting read, with many connections to people and places we know. But the author shaped the narrative to emphasize good end results if you remained a faithful conservative Mennonite.

Knowing many of the people involved, we felt that important details were omitted, and the truth was much more complicated and nuanced. It would not have dishonored the family or God to add more dimensions to the story.

I believe in grace for the truth of our lives.

We also read a book on marriage by a Mennonite woman. The author’s husband was distant, demanding, cold, and cruel. She doesn’t name his abuse or use those words—they are my conclusions from her stories. For example, he didn’t allow his wife to get medical help when she had severe postpartum depression, and he was very unhelpful around the house even during three difficult pregnancies and numerous house moves. He had another woman in his life, and it is unclear whether he limited his interaction to texting.

The author says she changed her husband and her marriage by trusting God and becoming more submissive and cheerful, altering her life in every way to cater to her husband’s wishes. For example, she gave up a successful home business for his sake and forced herself to cry less when she was depressed, which some of us have tried in the past and didn't have the superhuman strength to achieve.

It left me feeling like we weren’t hearing the full story, like wide swaths of truth were ignored, and others were manipulated. More troubling, the central message was this: a woman has the power to change her husband and a bad situation by doing everything right. Thus, logically, if the reader’s man and marriage don’t change, it’s her fault for somehow not doing the right things, despite her heroic efforts. There is no grace for bad days, overwhelming circumstances, and not knowing what on earth to do.

I am responsible for my choices as a person and a wife, and they affect my husband and our marriage. However, I am not God, and I don’t have the power to change my husband’s heart or the eventual outcomes, and any message otherwise is dangerous. I know many Christian women who have put incredible work and sacrifice into their marriages but were not able to sanctify their husbands or save their marriages.

So, when I run across Mennonite books that tell honest stories with a theme of faith and redemption, I joyfully pounce on them.

Two such books that I’ve reviewed in the past year are Turtle Heart by Luci Kinsinger and Peanut Butter and Dragon Wings by Shari Zook.

I was drawn to them because of the real-ness and the grace in the middle of brokenness and imperfection. In both of them, we see the process of growth. We don’t know everything, and so, beginning at Point A, we make choices out of where we are. Then things happen, and we learn, change, and grow. At the end, we are at Point B, and we are different than before. But we couldn’t reach the better and wiser end without going through the long, hard process.

Truth is your friend, and it walks hand in hand with grace. Grace is meaningless if we can’t tell the truth about how broken we are.

I would like to think Shari and Luci, with their authentic stories, determined honesty, and hard-won redemption, are signs that the cultural ship is turning. My daughter Emily's book, The Highway and Me and My Earl Grey Tea, fits this category as well.

To be clear, by “honest,” I don’t mean tasteless tell-alls that feel like someone vomiting in your lap. Nor do I insist that every detail and conversation must be verified and all sources cited. Or that there can be no conclusions drawn from past events.

Instead, I look for a general sense that the author is:

a) The same person in the public eye as they are in private. Their story has a ring of truth. You don’t smell a rat.

b) Committed to telling the truth even if it makes them or others look awkward or imperfect.

c) Ok with lingering questions and real-life outcomes that don’t make sense yet.

d) Looking far below the surface to figure out what motivated the events and the characters’ choices.

e) Not wedging events into a pre-planned religious formula.

f) Writing dialogue that sounds like real people talking.

g) Ok with being questioned about why and how they wrote what they did.

Justin Stauffer, the author of Charlie’s Boy--Into this House We're Born is no longer conservative Mennonite, but he used to be, so I feel that the discussion of honesty among Mennonite writers is relevant here.

Charlie’s Boy is based on the author’s own story. He says, “I do not market the book as fiction or an autobiography although one could make a strong argument for either. The genre is creative non-fiction, which I did not know existed until I was a student at Rosedale Bible College a few years ago. That knowledge was revolutionary for me as it allowed me to tell my story truthfully while leaving room for a lot of grace and nuance (two of my favorite things).”

It takes place in Alberta in the 1980s—if I calculated correctly—around the time that I first came to Oregon to teach school. One of many reasons that Justin’s story hit me in the gut was that the Mennonite culture in his home church was so similar to the one in Oregon—after all, they belonged to the same conference and used to get together for Annual Meetings and other events.

Coming from an Amish/Beachy past in the Midwest, I found that the Mennonite culture in the West was like nothing I had ever seen or imagined. People took the church rules so seriously that they made our strict church back home look lackadaisical by comparison. Everyone seemed watchful and cautious. Even youth-group girls talked solemnly about “personal convictions” they had about clothing or music. Back home, we discussed whether or not we wanted to stay Mennonite when we grew up. That subject was taboo in the youth group in Oregon.

A particular knit fabric—smooth, tightly knit, with small flowers--was popular among all the Mennonite ladies back then. They always had pointed collars and smooth gored skirts with no gathers, and long sleeves with a cuff or a bit of elastic at the wrist.

There’s a picture of Justin’s mother wearing just such a dress on his Facebook page, except hers didn’t have the pointed collar, and one look transported me back to that unsettling experience of being plunked, all wide-eyed and clueless, into this new culture.

I think that connection helped me feel the pain of Justin’s situation: his mom was the minister’s daughter. His dad was a renegade who drank too much alcohol and in every way didn’t fit in.

I try to imagine it, and it is almost too complicated and painful to examine closely: the dutiful daughter, belonging to the church and wanting so badly to please her powerful dad. And her husband is the antithesis of all she’s been taught. Her good behavior was supposed to lead to respect, belonging, a great marriage, and happy endings. She tries so hard to do everything right, and her husband is the plot twist that makes no sense at all.

Justin, the son, known as Muggsey, is caught not only between his parents but also the culture, the grandpa, the uncles, the friends, everyone. He seems yanked in all directions, misunderstood, forced to be a go-between. He has a deep and desperate longing to play sports. Dad would be ok with this. Mom would not. It hurts to read it.

No one follows the script. The good people are often cruel and confusing. The bad people reach the heart of a floundering boy with kindness and empathy. Dad, for all his failures and weaknesses, has the wisest insights of anyone. My husband read it and said, "You end up feeling sorry for everyone."

Being Mennonite, I frequently found myself yanked out of the story at first because I was trying to figure out exactly where this all happened, and when, and at what church, and who was who? Was Grandpa the notorious Mervin Bear, perhaps? (No.) Had I met Mom at the October meetings at Estacada in 1981? Which aunts and uncles belonged where, and what on earth was with the Hutterite references and all the nicknames for the children?

I finally decided to read the book like I read poetry, which is like canoeing across a lake. You skim over the top, absorbing the experience, without diving into the water to explore all the reeds and fish and mud.

In doing so, I felt the essence of the story surround me, the glassy water, the splash of the paddles, and the cattails at the edge. It was beautiful.

What I loved best was the sense that, even though the author crafted and shaped the narrative, I was reading something essentially authentic and true. He wasn’t hiding the truth to prop up a veneer or to prove a point. It felt true to life in beautiful and heartbreaking ways including, to be clear, both profanity and alcohol.

I wasn’t sure that the book, written in more of a literary style than I’m used to, would have a satisfying ending. So many real-life stories never end satisfactorily, but whatever I might say about authenticity and truth, I do like a book to resolve in the end.

This one wasn’t quite what I expected, but it tied up the loose ends and let me exhale.

I sent the author some questions, which he graciously answered. Here’s some of our exchange.

Me: I'm curious about the style. In some ways it's more literary-fiction than memoir or contemporary Christian fiction. A lot is left unsaid, and the reader is carried along more by the emotion of the story than the plot. This is true of the final chapter in particular. What influenced the decision to choose this style? Or did it develop organically without a conscious choice?

Justin: While I understand why folks may want to classify “Charlie’s Boy” as memoir or Christian fiction, I get a little uptight when those are the genres that are used to describe it. I love that you bring literary-fiction into the conversation and take it as a compliment—that is what I want it to be described as. I appreciate the controversy created by that term and before I began writing I contemplated what I could do to write something that couldn’t be fit neatly into one box or another. I had a fantastic English teacher who gave me a number of great prompts and it was during her literature class that I wrote the prologue and epilogue and settled on the voice in Muggsey’s head being central to the story. We read some amazing literature during that semester and I tried very hard to emulate some of the things I read and discovered.

Me: I am a Minnesota girl, and I like to know where I am and which way is north, both in real life and in fiction. I get confused easily with literary fiction and deep symbolism. However, also like a real Minnesotan, I like to have a thread to follow through a story, like a rope to follow to the barn in a blizzard, and the internal journey of Muggsey and the dad/mom/grandpa/church/God conflicts provided a strong rope to hang onto when I wasn't sure what was going on otherwise.

Justin: This comment is truly rewarding for me. I did try to leave some treasures buried in the words along the way, but more than anything, I wanted the questions to drive the proverbial train.

If you are familiar with “Blue Like Jazz” by Donald Miller, you will recall how the lack of resolution in Jazz music was what led to his choice of title. I loved that book and that idea really stuck with me. It was also especially poignant because BLJ was one of two precious books that Dad gifted me with. That lack of resolution has been the greatest constant in my life and I think it is what is lacking in most, but especially Christian, fiction. Folks seem to want their stories tied up in a neat bow and handed to them with full resolution. In my experience, life is never really that way.

So, as Diana and I waded through the thoughts and emotions the process of writing this story brought us, we became cognizant of several deep-seated desires relating to the end product. One, we wanted my story to be truthful without being hurtful. Two, we wanted every character to demonstrate a capacity for both heroism and villainy. Three, we want to ask questions that would stimulate conversations rather than try to give patented answers to questions that are bigger than we are. Four, we wanted the reader to experience some discomfort and reach the end with no resolution but a lot of hope in the central theme of redemption.

Me: Did you have any fears of mentioning cultural peculiarities that a non-Mennonite reader wouldn't "get"?

Justin: No, quite the opposite. Other than the tie in the first chapter, which I think begs the question, “What is going on here / this is weird,” I think they gave me an opportunity to build word pictures. Since most of my audience understands these peculiarities, I don’t know if they created a problem or added a positive layer of intrigue. I guess I’ll need an outside critic to answer that, but I haven’t received any real feedback regarding such issues (although I have received a lot of feedback from several non-Mennonite readers). Most folks have religious peculiarities of their own, so my assumption is that they made their own assumptions

Me: How did you handle the inevitable family members who felt that these things should not be spoken of?

Justin: It is difficult to navigate those waters—for sure! My family has been mostly gracious. The ones who took the greatest offense have been workable and I feel like we have been able to talk through most of the issues. The blowback I received was expected, some easy enough to navigate with a good heart-to-heart, some probably better left alone to soak for a while. Obviously, there was a lot of difficult material for my mom to read and relive, but she has been incredibly supportive and willing to let me share my story. My sister was a constant sounding board. She never wavered in encouraging me to finish and publish it. My Uncle Mark and Aunt Grace are the only other living characters who got a lot of mention as themselves and they have been amazing.

In a very expected irony, the greatest concerns were with my portrayal of Grampa. I feel like I was very gracious to him, others feel like I was less than gracious. Oddly enough, outside of family, everyone seems to think my family is awesome and they would love to meet them all. There were also some minor concerns of privacy and some concerns that folks in the community might view the family less favorably, but mostly, the ones who had concerns left me with, “It’s your story.”

Justin added, in a personal note, I have read much of your writing on social media, and I believe you are seeking the same things I am. Grace, hope, and intentional redemption.

Thank you, Justin.

You can order your copy of Charlie's Boy here.

Such a big topic for discussion--how much control we think we have over outcomes! And no easy pat answers. Thank you. As a former Minnesotan living in Oregon, I didn't realize it was a MN trait to need to know where I'm at and which way is north. No wonder I need to study a map before traveling anywhere. I have a rock in front of our house with sandblasted compass points to keep me aligned in the right direction. Sue R.

ReplyDeleteSue--I am obsessive about directions and knowing where I am, which is fine until you go to Lancaster, PA, like we did recently, and all the roads go diagonally and every which way. Garrison Keillor once wrote about Minnesotans traveling abroad and standing on street corners in Paris or London, holding a map and trying to figure out which way is North. I felt so understood.

DeleteI really like that you are bringing up this topic. I hadn’t thought about it, but you’re absolutely right that these stories where good is rewarded and evil is punished help to reinforce the Mennonite version of the prosperity gospel. (Also—see the R & S and CLP story papers…)

ReplyDeleteIn real life, bad people do good things sometimes and good people do bad things sometimes. One set of parents discipline their kids well (or at least it looks like it), only to have them go wild in adulthood. Another family looks like they’re raising a set of future monsters, but in the end they grow up and become healthy adults.

But the less cut-and-dried stories don’t get published as much.

I hadn't equated this mindset with the prosperity gospel until you and a couple of others mentioned it. Thank you.

DeleteSo very true that the less cut and dried stories don't get published as much.

Thank you for shining a light on this assumption in our Mennonite world - that by doing the right things we make the right outcomes. I am coming to terms with this kind of control and narrow view, and still struggling to learn HOW to do life more expansively. . . your clear assessment gives me some more insight and ways to be. . . THANK YOU.

ReplyDeleteYou're welcome, and thanks for sharing.

DeleteI think you may get some comfort and understanding out of this talk, given at a General Conference this past weekend. Life is at times confusing and inexplicable.

ReplyDeletehttps://www.churchofjesuschrist.org/study/general-conference/2022/04/41christofferson?lang=eng

Thanks for sharing!

DeleteI am honored that you mentioned Turtle Heart. Thank you. Honesty was so so important to me as I wrote that book, and in all my writing. Maybe the tide is changing and maybe outspoken Mennonite bloggers have something to do with that. I have often thought of that. Blogging gives a platform for saying things that might not be publishable anywhere else.

ReplyDeleteVery interesting insight. I know the internet and self-publishing have given voice to so many people who never had a voice or platform before.

DeleteOh Dorcas, how I would love to have a chat with you in person. You have such a knack for hitting nails right on their heads and saying things out loud that we all know we are thinking but we feel so unrighteous verbalizing them. Your mention of the infamous MB in your blog has reminded me of the powerful, far reaching influence that each one of us has that speaks into generations that will come after us. I have countless relatives that experienced the fruit of his influence. I looked up that word--Influence: "the capacity to have an effect on the character, development or behavior of someone or something" Thank you for shining the light on our cultural "prosperity gospel". God is God and may we never waver from that "knowing". Here is to speaking true Godliness into generations to come!

ReplyDelete